Our journey to explore the Hijaz Railway was inspired by a deep passion for preserving Saudi Arabia’s history. One of our team members, Richard Wilding, is a photographer who has dedicated his time to traveling across the kingdom, documenting its historical sites before they undergo restoration. His growing archive reflects his admiration for the rich cultural heritage of Saudi Arabia, and the Hijaz Railway was a natural next step in his mission. We were determined to include the railway and its trains in our upcoming project, capturing their legacy before any further changes took place.

After discussing with several tour guides, we knew that there was no better way to understand the significance of the railway than to see it with our own eyes. Although we’ve been in Saudi Arabia for over a year, we had yet to visit these remote desert locations. It felt like the perfect moment to scout this historical route for ourselves.

Part of our fascination stemmed from the famous scenes in the movie Lawrence of Arabia, where British forces famously sabotaged these very trains during the Arab Revolt. Watching those dramatic moments on screen left us eager to witness the remnants of the railway in real life, adding to our excitement for thias trip.

With that motivation, we set out on our location scouting trip to the Hijaz Railway, an iconic route that once connected the Arabian Peninsula to the broader world. Starting our journey in Medina, we aimed to track down the stations and remnants of the railway, hidden in the vast desert landscapes. Armed with a rented car and a sense of adventure, we were ready to uncover these forgotten pieces of history and bring them to light.

Medina Station: A Historic Gateway

Our first stop was Medina Station, situated less than a kilometer from the Prophet’s Mosque, making it a key destination for Muslim pilgrims. Built in 1908, this station was one of the largest and most important on the Hejaz Railway. With a facade adorned with 17 decorative arches, Medina Station is not only a functional space but also an architectural marvel. Nearby stands the Al Anbaria Mosque, constructed simultaneously with the station, forming a significant religious and logistical hub.

The station complex includes various facilities such as an operations center, rest houses for passengers and staff, a goods office, and even a water tower with a four-tank system. Despite being operational for a relatively short period before the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Medina Station played a vital role during World War I as a strategic point for the defense of the city. During our visit, we marveled at the restored trains and the rich history preserved at the station, which now serves as a museum.

The station’s historical significance stretches beyond its architecture. In 1916, during the Arab Revolt, Medina became a focal point of Ottoman resistance. Even after the Armistice of Mudros, the city remained under Ottoman control for months due to the leadership of General Fakhri Pasha. Standing on the station platform today, it’s easy to imagine the steam engines that once brought thousands of passengers to this gateway into the desert.

Muhit Station: A Strategic Outpost

From Medina, we traveled to Muhit Station, only 14 kilometers north of Medina. This station played a key role in the Ottoman defense of the railway, particularly during the Arab Revolt. The black basalt stone used in its construction gives the buildings a sturdy and imposing look. The station also includes a large barracks block capable of housing over 100 men, as well as a fortified defense post perched on a nearby hill.

This station saw its share of conflict, especially during attacks by Bedouin forces in June 1916. Its strategic location and fortifications helped the Ottomans maintain control of the station throughout much of the war. While the station is now quiet, with modern development encroaching upon its boundaries, it still stands as a reminder of the railway’s militarized past.

Hafira Station: A Battle-Scarred Site

We then made our way to Hafira Station, located 18 kilometers north of Muhit. The black basalt stone construction is similar to that of Muhit, and it features a two-story main building, barracks, and a water tower that once served as a critical resource for the station. The surrounding desert is vast, and the station’s isolation only adds to its haunting atmosphere.

Hafira was one of the first targets during the Arab Revolt, as Prince Faisal’s forces attempted to capture it in 1916. However, the presence of Ottoman armored trains made it difficult to overpower the station. This station’s strategic importance is further underscored by the fact that the nearby bridge was destroyed by Prince Ali’s forces in 1918 to disrupt Ottoman supply lines.

Usmani Railway Station: A Piece of Ottoman History

Usmani Railway Station was an essential part of the Ottoman-era railway network. The station still bears the architectural style typical of the period, with stone buildings and remnants of the tracks cutting through the desert. Standing at this station, you can feel the weight of history, imagining the bustling movement of goods and passengers that once passed through here.

Alhverh Train Station: A Desert Landmark

Next, we arrived at Alhverh Train Station, another stop on the Hijaz Railway. This station has largely been reclaimed by the desert, but some of the original structures remain standing. The station’s isolation in the vast desert adds to its quiet beauty, making it an ideal spot for capturing the essence of the railway’s history.

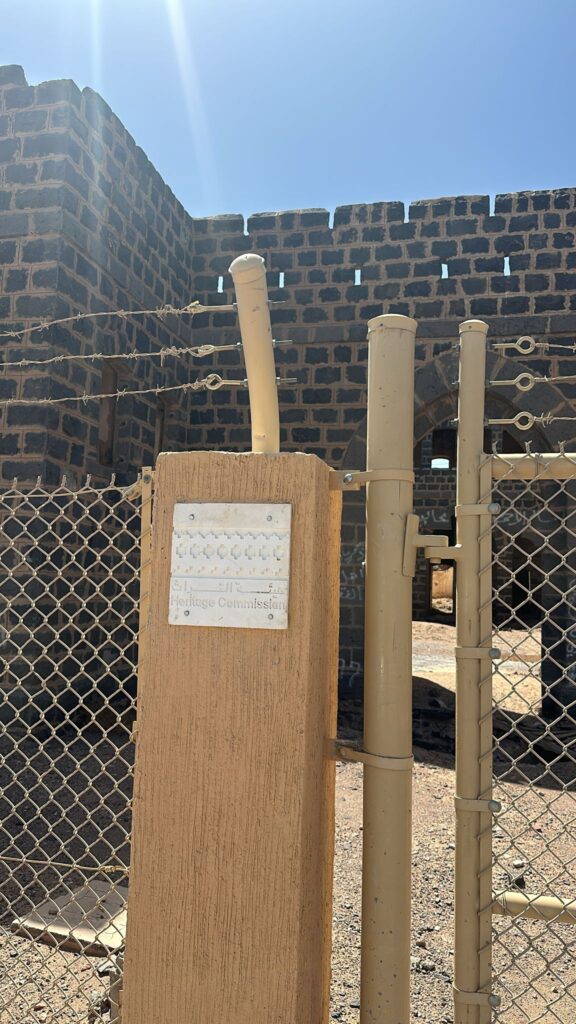

Buwat Station: A Fueling Stop and Defensive Outpost

Continuing north, we arrived at Buwat Station, 21 kilometers from Hafira. This station was crucial as a fuel depot, housing large quantities of wood and spare rails for the repair of damaged tracks. The station’s barracks are built around a central courtyard, and the surrounding desert is dotted with defensive positions and fortifications. A key defensive post is located on a nearby hill, providing a vantage point for Ottoman soldiers to watch over the railway.

Buwat was also a target during the Arab Revolt. In November 1917, a large force of Bedouin tribesmen, supported by French artillery, launched an attack on the station. Despite the initial success of the raid, Ottoman reinforcements arrived, and the station’s defenses held firm. This station’s well-preserved structures give a vivid impression of its role as a critical supply and defensive point during the war.

Bir Nassif Station: A Strategic Crossing

Our next stop was Bir Nassif Station, located 20 kilometers north of Buwat. This station, named after the local Nassif family, features a two-story black basalt stone building and barracks. Its water tower and cistern provided essential resources for the steam trains that passed through.

The nearby Wadi Reshad Bridge, a stunning 21-arch structure, is one of the most impressive remnants of the railway in this region. Though parts of the earth embankment have been washed away, the stone arches remain, offering a glimpse into the engineering feats of the Ottoman Empire. During the war, this bridge and the station played important roles in keeping the railway operational.

Al-Buwayr Station: A Glimpse Behind the Fence

As we approached Al-Buwayr Station, we were greeted by the sight of an old train, locked away behind a protective fence. Although access to the station is restricted, the trains are still visible from the outside, offering a unique glimpse into the past. Al-Buwayr once served as a critical stop along the railway, but today it stands in quiet solitude, its historic locomotives preserved as a testament to the station’s significance during the railway’s operational years.

Istabl Antar Station: Innacessible

Located deep in the desert, Istabl Antar Station is a remote stop along the Hijaz Railway. Once a key location during the railway’s operation, it now stands fully closed to the public, with no access for tourists. The station is surrounded by rugged terrain, and its historical significance remains locked away behind gates. While it’s inaccessible for viewing, its past as a critical point along the railway still echoes through the desert. The station’s isolation adds to its mystique, as it’s hidden from view and quietly withstanding the passage of time.

Al Ula Station: A Cultural Crossroads

Our journey then brought us to Al Ula, a place known for its archaeological significance and its connection to the Hijaz Railway. Al Ula Station, though now mostly abandoned, retains traces of its former life. The station here is surrounded by the breathtaking rock formations and ancient sites that have made Al Ula a focal point for tourism and cultural preservation in Saudi Arabia.

During the construction of the railway, Al Ula served as an important hub, not only for transportation but also for the cultural exchange between the various peoples of the region. Today, visitors can still see sections of the old railway tracks, standing as a testament to the railway’s impact on the region. The station blends almost seamlessly into the natural landscape, as if the railway itself had grown out of the desert.

Old Hejaz Train: Innacessible

At the location QM9W+WF8, Wayban 43479, deep in the heart of the desert, one of the old Hijaz trains remains untouched, lying in the middle of the desert sands. There is no station nearby, only the remnants of old train tracks that stretch across the landscape, silently marking the path the railway once took. This train is isolated and inaccessible by car, and reaching it requires a 14-kilometer hike from the nearest road. During our scouting trip, we were unable to visit this location, but these images, sourced from the internet, provide a rare look at this forgotten relic of history, standing alone amidst the sands.

As we continued our journey along the railway, tracing its path from station to station, we couldn’t help but reflect on the incredible history of this project. The Hijaz Railway was more than just a means of transportation—it was a symbol of modernity, ambition, and connection. Each station we visited told its own story, from the grand architecture of Medina to the quiet isolation of Hadiya, to the cultural crossroads of Al Ula.The tracks and bridges that still remain, half-buried in the sand, remind us that this was once a lifeline for pilgrims, soldiers, and traders alike. Though the railway has long since fallen into disrepair, its legacy lives on in the desert, where the wind still whispers through the old stations and the tracks lead off into the distance, disappearing into the horizon.Our team’s journey through the Hijaz Railway was both a scouting mission and a chance to step back in time. By visiting these sites and capturing their beauty, we hope to preserve their stories for future generations, ensuring that the legacy of the Hijaz Railway continues to inspire those who come after us.